Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Monday, January 30, 2006

Out & about, but still some doubt

After years of struggling with sexuality,

ex-Giant tells his story

By MICHAEL O'KEEFFE

DAILY NEWS SPORTS WRITER

Roy Simmons finally got the chance to let some sunshine into a life darkened by drugs and dishonesty. It was 1992 and Simmons, the former offensive lineman for the Giants and Redskins from 1979 to 1984, appeared on national television to tell Phil Donahue - and millions of viewers, including friends, relatives, ex-teammates and former girlfriends - a truth that he had been concealing for decades.

Simmons said he was gay. He said the pressure that came from concealing his sexuality for so long had cost him a promising career. It had prompted him to lie to loved ones, to cheat, to steal. It had turned him into a dope fiend, a thief, a gay prostitute.

But by 1992, Simmons had gone through a rehab stint and found religion, and he felt he was finally ready to tell the world the truth. The revelation didn't make him whole, though. It didn't magically establish a relationship with the daughter he had abandoned years before. It didn't make peace with the loved ones he had conned for so many years. And it sure didn't revive his NFL career.

So just weeks after his "Donahue" appearance, Simmons was back home in California, standing on the Golden Gate Bridge stoned on crack, trying to muster enough courage to throw himself into the San Francisco Bay.

Simmons didn't jump. Instead, he spent the next decade living in anonymity, sometimes binging on drugs, sometimes seeking help for his addictions. But things just seemed to go from bad to worse: In 1997, he learned he was HIV positive.

"My life, man, I wouldn't wish it on anybody," Simmons says.

Now Simmons, 49, wants to share the story of that life with the athletes who are still in the closet. Simmons is one of only three NFL players who have publicly announced their homosexuality - all after retirement (David Kopay came out in 1975 and Esera Tuaolo in 2002). Simmons estimates two or three members of every NFL team are gay, but sports remains America's last bastion of homophobia, and the NFL doesn't appear to be in any rush to make its homosexuals feel welcome.

"In the NFL," Simmons says, "there is nothing worse than being gay. You can beat your wife, but you better not be gay."

That's why so many gay athletes, Simmons says, live on the down low, having anonymous and often unprotected sex with other men. Those secret lives increase the chances they'll become infected with the AIDS virus and pass it on to lovers, male and female. It also makes them more susceptible to alcoholism, drug abuse, anything that might numb their pain.

Simmons says he has contacted the NFL and its union to share his story with the players, but neither has taken him up on his offer. "I know I can help stop someone from going through what I went through," Simmons says. "I've been there. I've had two jobs in my life - football and running. Mostly running."

NFL spokesman Greg Aiello says he isn't aware of any specific offer from Simmons, adding that the league might consider bringing him in for its annual rookie symposium. But Simmons has already found a much broader audience: He's written a book with author Damon DiMarco, "Out of Bounds," that tells the story of his tortured life.

Simmons has been sober and celibate for several years now, he says, and he's healthier than he's been in decades. His longtime friend, Jimmy Hester, introduced him to a naturopathic healer in Martha's Vineyard, where he lives with Hester, who put him on a strict detoxification program and vitamin regimen. But the doctor, Roni DeLuz, says Simmons carries so much pain in his psyche that he'll never be completely right.

"I don't think Roy will ever be okay," she says. "Every day will be a struggle for him. He could relapse into drugs or other self-destructive behavior. But every time he tells his story, it helps him heal. You can't heal yourself until you are honest with yourself."

* * *

To be Roy Simmons is to live in a world of contradictions. Simmons was a fast, strong athlete who played the most macho position in pro sports; he was also a drag queen in size 16 shoes who loved to strut up and down the streets of San Francisco. Simmons was paid big money to play football; he was also a homeless prostitute who earned $15 a trick. Simmons says he accepts that he is gay; he also told televangelist Pat Robertson and his "700 Club" audience just last year that homosexuality is against God's will.

"If you've been through what Roy has been through, you'd be conflicted, too," says Hester, an entertainment publicist who became friends with Simmons when Hester was 13 and working as at a Jersey restaurant popular with the Giants.

Simmons grew up up in Savannah, Ga., raised mostly by his grandmother. His father lived nearby but wasn't a factor in his life. The family was poor so his mother moved to New York to work as a domestic, and although she regularly sent money home, she was absent for large chunks of his life, too.

Simmons was 11 when he says his life began to spin out of control. A neighbor hired him to do some chores around her house, then left him alone with her husband. The husband, "Travis," called Simmons into a bedroom and pulled down his pants. Then he raped the boy.

Simmons says that it was the moment that has defined his life. He writes in his book that he hated Travis, but he says he was also attracted to him. Simmons and his neighbor had other sexual encounters after that rape; years later, after his first season with the Giants, Simmons says he and a buddy ran into Travis at a Savannah gay bar and had "revenge" sex with him.

"Maybe a part of me saw him as the person I'd sensed I was missing all along," Simmons writes.

Simmons spent his teen years having sex with boys even as he cultivated a relationship with the girl who would eventually become the mother of his child. "In my head I had this vision of my girl dressed up all pretty in white on our wedding day," he writes.

But there was one thing Simmons wasn't confused about: football. He was a big, strong all-city football player who worked hard to master the game. His skills attracted recruiters from big-time programs who offered him girls, clothes, cars and envelopes full of $100 bills. In the end, Simmons signed on with Georgia Tech, even though the only thing that school offered was an education and an opportunity to play ball.

At Georgia Tech, Simmons - now nicknamed "Sugar Bear" because of his sweet personality - proved to be an outstanding football player. He joined a fraternity, smoked a lot of pot and fooled around with girls. He also became a regular at a gay bathhouse near campus.

Simmons was drafted by the Giants in the eighth round of the 1979 draft and moved into New York's gay scene, becoming a regular at the city's gay clubs and bathhouses. He'd hire hustlers and take them to hotel rooms; he says he even had a Tanqueray-and-Quaalude-fueled fling with a teammate one night.

Simmons suspects they weren't the only teammates who got together: "I suspected that two of my teammates were fooling around with each other," he writes in his book. "They were way too buddy-buddy with each other for it to be a purely heterosexual friendship."

Drugs, he says, were everywhere. He says he saw one teammate snort coke just before a game; he saw others freebasing at a party. Simmons became a fixture of what he calls the Giants' drug clique and threw wild dope and sex parties. One party drew not just teammates but members of the Jets, Nets and now-defunct New York Cosmos and New Jersey Generals as well. "Cocaine, reefer, uppers, downers, you name it," Simmons writes, "it was on the coffee table, laid out like a buffet."

Simmons was juggling affairs with several women, including one who became pregnant and gave birth to a girl she named Kara. He began a serious relationship with a man he met at a bathhouse. The alcohol and the drugs diminished his performance on the field, and he was demoted from starter to sub. Simmons finally snapped, worn out by the pressure of his hidden sex life and the demands of his family, the drinking and drugging. Just before the 1982 season, he told coach Ray Perkins he wanted to take a year off.

He spent the year as a baggage handler at JFK and tried to come back the following season. But new coach Bill Parcells had no use for Simmons and he was cut. The Redskins picked him up and he went with the team to Super Bowl XVIII in Tampa, where the Skins got waxed by the Los Angeles Raiders.

Simmons was cut by the Redskins in '84 - the freebasing habit he says he picked up in D.C. didn't help his career - and had a brief stint with the USFL's Jacksonville Bulls. The USFL might have been second-tier, but it was big league when it came to drugs and drinking, Simmons says. "On some occasions I was blowing a grand or more a day on drugs," he writes.

But the Bulls folded and Simmons' career was over by the end of the 1985 season. Simmons retired from football with nothing to show for it except a voracious drug habit and a hidden sex life.

* * *

Simmons moved to Newark after his football career ended and although he was still drinking heavily and using drugs, he fell in with a group of professional gay men. It was a community that looked after each other and though Simmons was still in the closet, he felt at peace.

But in 1990, Simmons confided to a cousin that he was gay. The cousin told one of Simmons' former girlfriends. The word spread to other relatives and friends. Simmons, angry and humiliated, withdrew $10,000 from his bank and flew to San Francisco. He became a regular in that city's bathhouses and gay clubs. He even started dressing up in drag - all 290 pounds of him.

Simmons finally bottomed out in California. He blew his money on booze and drugs and went on welfare. He spent five months in prison for shoplifting. He prostituted himself for $15, $20 or a few lines of cocaine.

He became a large, mean drug addict who lashed out at anyone who slighted him. He says he beat and stabbed one guy who ripped him off in a drug deal, leaving his bleeding, wheezing body in a filthy alley. He still doesn't know if the man lived or died.

Simmons finally entered a drug rehab program and started attending a church. Then he appeared on "Donahue," tempted by the prospect of a free trip back East. But Simmons was not prepared for the consequences of his national outing. Friends and relatives who were not aware of his sexuality were shocked. Former teammates asked if he was high. None of them congratulated Simmons; none of them said, "What you did took guts."

A month later, he had traded most of his possessions - and his roommate's - for crack. He drove to the Golden Gate Bridge and prepared to jump. But then he heard his grandmother's voice telling him that people who commit suicide go straight to hell.

He called Jimmy Hester, who arranged for Simmons to return to Long Island, where Simmons' mother and other family members lived, and he entered an intensive drug program. He had relapses and he contracted HIV, but Simmons says he feels better now than he has in decades. The book has been cathartic, he says, and he hopes his message might get through to other struggling athletes. He's even established a relationship with his daughter, Kara, who is now 24 years old and recently graduated from college.

"I feel good," he says. "Not wonderful. I'm working with a therapist. I'm hoping if I can understand what I went through and I can explain it to other guys, maybe those other guys won't have to suffer like I did."

Originally published on January 29, 2006

ex-Giant tells his story

By MICHAEL O'KEEFFE

DAILY NEWS SPORTS WRITER

Roy Simmons finally got the chance to let some sunshine into a life darkened by drugs and dishonesty. It was 1992 and Simmons, the former offensive lineman for the Giants and Redskins from 1979 to 1984, appeared on national television to tell Phil Donahue - and millions of viewers, including friends, relatives, ex-teammates and former girlfriends - a truth that he had been concealing for decades.

Simmons said he was gay. He said the pressure that came from concealing his sexuality for so long had cost him a promising career. It had prompted him to lie to loved ones, to cheat, to steal. It had turned him into a dope fiend, a thief, a gay prostitute.

But by 1992, Simmons had gone through a rehab stint and found religion, and he felt he was finally ready to tell the world the truth. The revelation didn't make him whole, though. It didn't magically establish a relationship with the daughter he had abandoned years before. It didn't make peace with the loved ones he had conned for so many years. And it sure didn't revive his NFL career.

So just weeks after his "Donahue" appearance, Simmons was back home in California, standing on the Golden Gate Bridge stoned on crack, trying to muster enough courage to throw himself into the San Francisco Bay.

Simmons didn't jump. Instead, he spent the next decade living in anonymity, sometimes binging on drugs, sometimes seeking help for his addictions. But things just seemed to go from bad to worse: In 1997, he learned he was HIV positive.

"My life, man, I wouldn't wish it on anybody," Simmons says.

Now Simmons, 49, wants to share the story of that life with the athletes who are still in the closet. Simmons is one of only three NFL players who have publicly announced their homosexuality - all after retirement (David Kopay came out in 1975 and Esera Tuaolo in 2002). Simmons estimates two or three members of every NFL team are gay, but sports remains America's last bastion of homophobia, and the NFL doesn't appear to be in any rush to make its homosexuals feel welcome.

"In the NFL," Simmons says, "there is nothing worse than being gay. You can beat your wife, but you better not be gay."

That's why so many gay athletes, Simmons says, live on the down low, having anonymous and often unprotected sex with other men. Those secret lives increase the chances they'll become infected with the AIDS virus and pass it on to lovers, male and female. It also makes them more susceptible to alcoholism, drug abuse, anything that might numb their pain.

Simmons says he has contacted the NFL and its union to share his story with the players, but neither has taken him up on his offer. "I know I can help stop someone from going through what I went through," Simmons says. "I've been there. I've had two jobs in my life - football and running. Mostly running."

NFL spokesman Greg Aiello says he isn't aware of any specific offer from Simmons, adding that the league might consider bringing him in for its annual rookie symposium. But Simmons has already found a much broader audience: He's written a book with author Damon DiMarco, "Out of Bounds," that tells the story of his tortured life.

Simmons has been sober and celibate for several years now, he says, and he's healthier than he's been in decades. His longtime friend, Jimmy Hester, introduced him to a naturopathic healer in Martha's Vineyard, where he lives with Hester, who put him on a strict detoxification program and vitamin regimen. But the doctor, Roni DeLuz, says Simmons carries so much pain in his psyche that he'll never be completely right.

"I don't think Roy will ever be okay," she says. "Every day will be a struggle for him. He could relapse into drugs or other self-destructive behavior. But every time he tells his story, it helps him heal. You can't heal yourself until you are honest with yourself."

* * *

To be Roy Simmons is to live in a world of contradictions. Simmons was a fast, strong athlete who played the most macho position in pro sports; he was also a drag queen in size 16 shoes who loved to strut up and down the streets of San Francisco. Simmons was paid big money to play football; he was also a homeless prostitute who earned $15 a trick. Simmons says he accepts that he is gay; he also told televangelist Pat Robertson and his "700 Club" audience just last year that homosexuality is against God's will.

"If you've been through what Roy has been through, you'd be conflicted, too," says Hester, an entertainment publicist who became friends with Simmons when Hester was 13 and working as at a Jersey restaurant popular with the Giants.

Simmons grew up up in Savannah, Ga., raised mostly by his grandmother. His father lived nearby but wasn't a factor in his life. The family was poor so his mother moved to New York to work as a domestic, and although she regularly sent money home, she was absent for large chunks of his life, too.

Simmons was 11 when he says his life began to spin out of control. A neighbor hired him to do some chores around her house, then left him alone with her husband. The husband, "Travis," called Simmons into a bedroom and pulled down his pants. Then he raped the boy.

Simmons says that it was the moment that has defined his life. He writes in his book that he hated Travis, but he says he was also attracted to him. Simmons and his neighbor had other sexual encounters after that rape; years later, after his first season with the Giants, Simmons says he and a buddy ran into Travis at a Savannah gay bar and had "revenge" sex with him.

"Maybe a part of me saw him as the person I'd sensed I was missing all along," Simmons writes.

Simmons spent his teen years having sex with boys even as he cultivated a relationship with the girl who would eventually become the mother of his child. "In my head I had this vision of my girl dressed up all pretty in white on our wedding day," he writes.

But there was one thing Simmons wasn't confused about: football. He was a big, strong all-city football player who worked hard to master the game. His skills attracted recruiters from big-time programs who offered him girls, clothes, cars and envelopes full of $100 bills. In the end, Simmons signed on with Georgia Tech, even though the only thing that school offered was an education and an opportunity to play ball.

At Georgia Tech, Simmons - now nicknamed "Sugar Bear" because of his sweet personality - proved to be an outstanding football player. He joined a fraternity, smoked a lot of pot and fooled around with girls. He also became a regular at a gay bathhouse near campus.

Simmons was drafted by the Giants in the eighth round of the 1979 draft and moved into New York's gay scene, becoming a regular at the city's gay clubs and bathhouses. He'd hire hustlers and take them to hotel rooms; he says he even had a Tanqueray-and-Quaalude-fueled fling with a teammate one night.

Simmons suspects they weren't the only teammates who got together: "I suspected that two of my teammates were fooling around with each other," he writes in his book. "They were way too buddy-buddy with each other for it to be a purely heterosexual friendship."

Drugs, he says, were everywhere. He says he saw one teammate snort coke just before a game; he saw others freebasing at a party. Simmons became a fixture of what he calls the Giants' drug clique and threw wild dope and sex parties. One party drew not just teammates but members of the Jets, Nets and now-defunct New York Cosmos and New Jersey Generals as well. "Cocaine, reefer, uppers, downers, you name it," Simmons writes, "it was on the coffee table, laid out like a buffet."

Simmons was juggling affairs with several women, including one who became pregnant and gave birth to a girl she named Kara. He began a serious relationship with a man he met at a bathhouse. The alcohol and the drugs diminished his performance on the field, and he was demoted from starter to sub. Simmons finally snapped, worn out by the pressure of his hidden sex life and the demands of his family, the drinking and drugging. Just before the 1982 season, he told coach Ray Perkins he wanted to take a year off.

He spent the year as a baggage handler at JFK and tried to come back the following season. But new coach Bill Parcells had no use for Simmons and he was cut. The Redskins picked him up and he went with the team to Super Bowl XVIII in Tampa, where the Skins got waxed by the Los Angeles Raiders.

Simmons was cut by the Redskins in '84 - the freebasing habit he says he picked up in D.C. didn't help his career - and had a brief stint with the USFL's Jacksonville Bulls. The USFL might have been second-tier, but it was big league when it came to drugs and drinking, Simmons says. "On some occasions I was blowing a grand or more a day on drugs," he writes.

But the Bulls folded and Simmons' career was over by the end of the 1985 season. Simmons retired from football with nothing to show for it except a voracious drug habit and a hidden sex life.

* * *

Simmons moved to Newark after his football career ended and although he was still drinking heavily and using drugs, he fell in with a group of professional gay men. It was a community that looked after each other and though Simmons was still in the closet, he felt at peace.

But in 1990, Simmons confided to a cousin that he was gay. The cousin told one of Simmons' former girlfriends. The word spread to other relatives and friends. Simmons, angry and humiliated, withdrew $10,000 from his bank and flew to San Francisco. He became a regular in that city's bathhouses and gay clubs. He even started dressing up in drag - all 290 pounds of him.

Simmons finally bottomed out in California. He blew his money on booze and drugs and went on welfare. He spent five months in prison for shoplifting. He prostituted himself for $15, $20 or a few lines of cocaine.

He became a large, mean drug addict who lashed out at anyone who slighted him. He says he beat and stabbed one guy who ripped him off in a drug deal, leaving his bleeding, wheezing body in a filthy alley. He still doesn't know if the man lived or died.

Simmons finally entered a drug rehab program and started attending a church. Then he appeared on "Donahue," tempted by the prospect of a free trip back East. But Simmons was not prepared for the consequences of his national outing. Friends and relatives who were not aware of his sexuality were shocked. Former teammates asked if he was high. None of them congratulated Simmons; none of them said, "What you did took guts."

A month later, he had traded most of his possessions - and his roommate's - for crack. He drove to the Golden Gate Bridge and prepared to jump. But then he heard his grandmother's voice telling him that people who commit suicide go straight to hell.

He called Jimmy Hester, who arranged for Simmons to return to Long Island, where Simmons' mother and other family members lived, and he entered an intensive drug program. He had relapses and he contracted HIV, but Simmons says he feels better now than he has in decades. The book has been cathartic, he says, and he hopes his message might get through to other struggling athletes. He's even established a relationship with his daughter, Kara, who is now 24 years old and recently graduated from college.

"I feel good," he says. "Not wonderful. I'm working with a therapist. I'm hoping if I can understand what I went through and I can explain it to other guys, maybe those other guys won't have to suffer like I did."

Originally published on January 29, 2006

Secrets and lies

Belinda Oaten has suffered the very public outing of her husband's gay affair. But she is not alone. Diane Taylor talks to the women whose spouses hid their homosexuality

Friday January 27, 2006

The Guardian

The political fallout from revelations that Mark Oaten spent time with a male prostitute was swift and brutal. Even before the News of the World, which exposed him, had hit the streets last Sunday, he resigned as the Liberal Democrats' home affairs spokesman. But the extent of the damage to his 13-year marriage is less clear.

Holed up somewhere snowy in Europe, Oaten's wife, Belinda, 37, is saying little apart from the fact that she is "incredibly angry" and views her husband's behaviour as "the ultimate betrayal". One newspaper report yesterday quoted "a friend of the couple" saying that the marriage is at an end as far as Belinda is concerned.

But what of couples who do not find themselves in the public eye when disclosures about extramarital gay dalliances surface? For a wife who has had no inkling that her spouse was anything other than heterosexual, is it better or worse than finding out that he has been unfaithful with a woman? And is it possible to sustain a marriage after her husband's proclivities are revealed, or is parting inevitable?

There are no statistics on the fate of such marriages in the UK, but according to the Straight Spouse Network, which has its headquarters in the US, where, it estimates, about two million gay men and lesbian women are married to straight partners, roughly a third of couples break up immediately, a third remain together for a year and then split, while the remaining third try to stay together. After three years, half this latter group are still together.

Women who have found themselves in Belinda Oaten's situation say that there can be fleeting relief when they discover that another man is involved if they had suspected their husband was having an affair with a woman, which they would have found more threatening. In the longer term, however, the feeling of being doubly deceived can be overwhelming. Not only have they been fooled about a relationship they thought was monogamous, but they have also been fooled about their partner's sexuality.

Helen, 58, discovered that her husband, Tom, was gay eight years ago. They had been married for 24 years before she found out where his sexual preferences lay. But the problems in her marriage predated that discovery by some time. "The gay partner may blame the straight partner if things aren't going right in the marriage," she says. "The straight partner can be made to feel deficient or unattractive.

"I tried to fix things but floundered because I didn't know what I was supposed to be fixing. It's like asking a doctor to cure a headache when what you've got is a broken leg."

Helen found an amorous email he had written. She assumed it had been written to another woman and, when she confronted him, he allowed her to carry on thinking that. Then she discovered links on the computer to gay chatrooms. Even then, she didn't realise her husband was gay. But during a subsequent row, she shouted: "And you visit gay chatrooms too!"

"At that moment I knew," says Helen. "The colour drained out of his face. 'What do you think?' he said. 'Are you telling me you're gay?' I asked. He nodded and I felt strangely relieved."

In fact, Helen felt they were able to communicate honestly for the first time in years: "He told me that he had known from the age of nine that he was gay but didn't want to be gay."

At the time of Helen's discovery, Tom had never had a relationship with a man. They have since parted amicably and Tom has had a couple of short-lived relationships with men. After some initial distress, their two adult children have accepted the situation.

"Tom said that when he met me, he didn't feel the need to be gay, but he was always very distant. Our sex life was more a celebration of the male body than an expression of emotional closeness between us," says Helen. "I think women who are secretly lesbian in a straight marriage have a harder time having sex with their husbands than gay men in a straight marriage. Men are more able to separate the emotional from the physical and are turned on by the idea of sex even if they're not turned on by the woman's body."

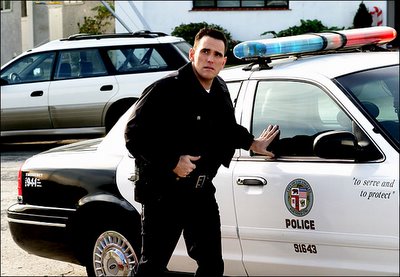

Max, a 30-year-old male prostitute, says that the vast majority of his clients are, like Tom, married with children. "Occasionally, I'll get a call from an openly gay man who wants to meet up for sex, but most of my clients are married with children.

"I had one client who told his mother that he was gay. She was so upset that he got married to keep his mother happy. I think that some of the married men who come to me are not only responding to pressure from society to conform to a straight lifestyle, but are also in denial about their sexuality. With men like me, they can express themselves openly."

Interestingly, Max's secretly gay clients don't only seek him out for sexual release, he says, but also for emotional succour. "I have lost count of the number of married men who have cried when they visit me. I've done a basic skills course in counselling so that I can offer them support," he says. "People are saying that men like Mark Oaten are bastards, but in fact they're victims. They're pressurised by society into conforming to a sexuality they don't want to be a part of. I feel sorry for Mark and his wife, and I condemn the man who went to the News of the World with the story. I would never spill the beans on a client."

Amity Pierce Buxton, who heads the Straight Spouse Network (which has a UK branch), is happily remarried after her first husband came out after 25 years. They remained friends until he died three years ago. "The important thing is to go slowly when these situations arise," she says. "Couples need to communicate with each other honestly so that, even if they separate, they can have a relationship based on truth."

Like Helen and Amity, Pat had no idea that her husband, Mike, was having affairs with both men and women, which began within a year of marriage. Both in their late 50s, they recently separated after 27 years. She began picking up clues six years ago when she caught him downloading gay porn. "He told me he was downloading gay rather than straight porn because it was less likely to have viruses in it. His behaviour is similar to that of an alcoholic who will say and do anything - and then believe it," she says.

The legacy of the revelations about her husband's behaviour, when she accepted the truth after an initial period of denial, has been very difficult. "Apart from the emotional cost, the ramifications are pretty unbelievable," she says. "If a man is unfaithful to his wife with another man, it doesn't count in law as adultery. I had always thought that we would have a certain amount of money for our retirement. But now he's moved out, there are two separate households to run so there's less disposable income."

Worst of all, says Pat, is the awareness of what has gone: "When your husband dies, you lose your future with him. But when something like this comes out, you lose your past because it was all based on lies."

Moving on is often far from straightforward for the woman. While her husband can begin a new life in the gay community, she is faced with whether or not to explain the the real reason for the marital break-up. "As our partners come out of the closet," says Helen, "they slam the door on a new closet inside which we straight spouses find ourselves trapped".

· Some names have been changed. Information from straightspouse.org or contact ever@str8s.org for UK branch details.

Friday January 27, 2006

The Guardian

The political fallout from revelations that Mark Oaten spent time with a male prostitute was swift and brutal. Even before the News of the World, which exposed him, had hit the streets last Sunday, he resigned as the Liberal Democrats' home affairs spokesman. But the extent of the damage to his 13-year marriage is less clear.

Holed up somewhere snowy in Europe, Oaten's wife, Belinda, 37, is saying little apart from the fact that she is "incredibly angry" and views her husband's behaviour as "the ultimate betrayal". One newspaper report yesterday quoted "a friend of the couple" saying that the marriage is at an end as far as Belinda is concerned.

But what of couples who do not find themselves in the public eye when disclosures about extramarital gay dalliances surface? For a wife who has had no inkling that her spouse was anything other than heterosexual, is it better or worse than finding out that he has been unfaithful with a woman? And is it possible to sustain a marriage after her husband's proclivities are revealed, or is parting inevitable?

There are no statistics on the fate of such marriages in the UK, but according to the Straight Spouse Network, which has its headquarters in the US, where, it estimates, about two million gay men and lesbian women are married to straight partners, roughly a third of couples break up immediately, a third remain together for a year and then split, while the remaining third try to stay together. After three years, half this latter group are still together.

Women who have found themselves in Belinda Oaten's situation say that there can be fleeting relief when they discover that another man is involved if they had suspected their husband was having an affair with a woman, which they would have found more threatening. In the longer term, however, the feeling of being doubly deceived can be overwhelming. Not only have they been fooled about a relationship they thought was monogamous, but they have also been fooled about their partner's sexuality.

Helen, 58, discovered that her husband, Tom, was gay eight years ago. They had been married for 24 years before she found out where his sexual preferences lay. But the problems in her marriage predated that discovery by some time. "The gay partner may blame the straight partner if things aren't going right in the marriage," she says. "The straight partner can be made to feel deficient or unattractive.

"I tried to fix things but floundered because I didn't know what I was supposed to be fixing. It's like asking a doctor to cure a headache when what you've got is a broken leg."

Helen found an amorous email he had written. She assumed it had been written to another woman and, when she confronted him, he allowed her to carry on thinking that. Then she discovered links on the computer to gay chatrooms. Even then, she didn't realise her husband was gay. But during a subsequent row, she shouted: "And you visit gay chatrooms too!"

"At that moment I knew," says Helen. "The colour drained out of his face. 'What do you think?' he said. 'Are you telling me you're gay?' I asked. He nodded and I felt strangely relieved."

In fact, Helen felt they were able to communicate honestly for the first time in years: "He told me that he had known from the age of nine that he was gay but didn't want to be gay."

At the time of Helen's discovery, Tom had never had a relationship with a man. They have since parted amicably and Tom has had a couple of short-lived relationships with men. After some initial distress, their two adult children have accepted the situation.

"Tom said that when he met me, he didn't feel the need to be gay, but he was always very distant. Our sex life was more a celebration of the male body than an expression of emotional closeness between us," says Helen. "I think women who are secretly lesbian in a straight marriage have a harder time having sex with their husbands than gay men in a straight marriage. Men are more able to separate the emotional from the physical and are turned on by the idea of sex even if they're not turned on by the woman's body."

Max, a 30-year-old male prostitute, says that the vast majority of his clients are, like Tom, married with children. "Occasionally, I'll get a call from an openly gay man who wants to meet up for sex, but most of my clients are married with children.

"I had one client who told his mother that he was gay. She was so upset that he got married to keep his mother happy. I think that some of the married men who come to me are not only responding to pressure from society to conform to a straight lifestyle, but are also in denial about their sexuality. With men like me, they can express themselves openly."

Interestingly, Max's secretly gay clients don't only seek him out for sexual release, he says, but also for emotional succour. "I have lost count of the number of married men who have cried when they visit me. I've done a basic skills course in counselling so that I can offer them support," he says. "People are saying that men like Mark Oaten are bastards, but in fact they're victims. They're pressurised by society into conforming to a sexuality they don't want to be a part of. I feel sorry for Mark and his wife, and I condemn the man who went to the News of the World with the story. I would never spill the beans on a client."

Amity Pierce Buxton, who heads the Straight Spouse Network (which has a UK branch), is happily remarried after her first husband came out after 25 years. They remained friends until he died three years ago. "The important thing is to go slowly when these situations arise," she says. "Couples need to communicate with each other honestly so that, even if they separate, they can have a relationship based on truth."

Like Helen and Amity, Pat had no idea that her husband, Mike, was having affairs with both men and women, which began within a year of marriage. Both in their late 50s, they recently separated after 27 years. She began picking up clues six years ago when she caught him downloading gay porn. "He told me he was downloading gay rather than straight porn because it was less likely to have viruses in it. His behaviour is similar to that of an alcoholic who will say and do anything - and then believe it," she says.

The legacy of the revelations about her husband's behaviour, when she accepted the truth after an initial period of denial, has been very difficult. "Apart from the emotional cost, the ramifications are pretty unbelievable," she says. "If a man is unfaithful to his wife with another man, it doesn't count in law as adultery. I had always thought that we would have a certain amount of money for our retirement. But now he's moved out, there are two separate households to run so there's less disposable income."

Worst of all, says Pat, is the awareness of what has gone: "When your husband dies, you lose your future with him. But when something like this comes out, you lose your past because it was all based on lies."

Moving on is often far from straightforward for the woman. While her husband can begin a new life in the gay community, she is faced with whether or not to explain the the real reason for the marital break-up. "As our partners come out of the closet," says Helen, "they slam the door on a new closet inside which we straight spouses find ourselves trapped".

· Some names have been changed. Information from straightspouse.org or contact ever@str8s.org for UK branch details.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

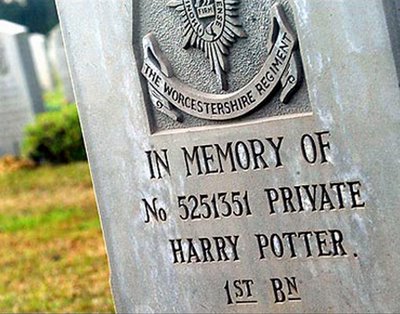

Military Officers Discharged under Gay Policy

Hundreds of military officers, health care professionals discharged under gay policy

WASHINGTON -- Hundreds of officers and health care professionals have been discharged in the past 10 years under the Pentagon's policy on gays, a loss that while relatively small in numbers involves troops who are expensive for the military to educate and train.

The 350 or so affected are a tiny fraction of the 1.4 million members of the uniformed services and about 3.5 percent of the more than 10,000 people discharged under the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy since its inception in 1994.

But many were military school graduates or service members who went to medical school at the taxpayers' expense _ troops not as easily replaced by a nation at war that is struggling to fill its enlistment quotas.

"You don't just go out on the street tomorrow and pluck someone from the general population who has an Air Force education, someone trained as a physician, someone who bleeds Air Force blue, who is willing to serve, and that you can put in Iraq tomorrow," said Beth Schissel, who graduated from the Air Force Academy in 1989 and went on to medical school.

Schissel was forced out of the military after she acknowledged that she was gay.

According to figures compiled by the Pentagon and released by the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military, Schissel is one of 244 medical and health professionals discharged from 1994 through 2003 under the policy that allows gays and lesbians to serve as long as they abstain from homosexual activity and do not disclose their sexual orientation. Congress approved the policy in 1993.

There were 137 officers discharged during that period. The database compiled by the Pentagon does not include names, but it appears that about 30 of the medical personnel who were discharged may also be included in the list of officers.

The center _ a research unit of the Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research of the University of California _ promotes analysis of the issue of gays in the military.

"These discharges comprise a very small percentage of the total and should be viewed in that context," said Lt. Col. Ellen Krenke, a Pentagon spokeswoman. She added that troops discharged under the law can continue to serve their country by becoming a private military contractor or working for other federal agencies.

Opponents of the policy on gays acknowledge that the number of those discharged is small. But they say the policy exacerbates a shortage of medical specialists in the military when they are needed the most.

Late last year Army officials acknowledged in a congressional hearing that they are seeing shortfalls in key medical specialties.

"What advantage is the military getting by firing brain surgeons at the very time our wounded soldiers aren't receiving the medical care they need?" said Aaron Belkin, associate professor of political science at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Overall, the number of discharges has gone down in recent years.

"When we're at war, commanders know that gay personnel are just as important as any other personnel," said Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow at the Center. He said that in some instances commanders knew someone in their unit was gay but ignored it.

The overall discharges peaked in 2000 and 2001, on the heels of the 1999 murder of Pfc. Barry Winchell, who was bludgeoned to death by a fellow soldier at Fort Campbell, Ky., who believed Winchell was gay. About one-sixth of the discharges in 2001 were at that base.

Officials did not provide estimates on the cost of a military education or one for medical personnel. However, according to the private American Medical Student Association, average annual tuition and fees at public and private U.S. medical schools in 2002 were $14,577 and $30,960, respectively.

Early last year the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, estimated it cost the Pentagon nearly $200 million to recruit and train replacements for the nearly 9,500 troops that had to leave the military because of the policy. The losses included hundreds of highly skilled troops, including translators, between 1994 through 2003.

Opponents of the policy are backing legislation in the House sponsored by Rep. Marty Meehan, D-Mass., that would repeal the law. But that bill _ with 107 co-sponsors _ is considered a longshot in the Republican-controlled House.

Copyright 2006 Associated Press.

WASHINGTON -- Hundreds of officers and health care professionals have been discharged in the past 10 years under the Pentagon's policy on gays, a loss that while relatively small in numbers involves troops who are expensive for the military to educate and train.

The 350 or so affected are a tiny fraction of the 1.4 million members of the uniformed services and about 3.5 percent of the more than 10,000 people discharged under the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy since its inception in 1994.

But many were military school graduates or service members who went to medical school at the taxpayers' expense _ troops not as easily replaced by a nation at war that is struggling to fill its enlistment quotas.

"You don't just go out on the street tomorrow and pluck someone from the general population who has an Air Force education, someone trained as a physician, someone who bleeds Air Force blue, who is willing to serve, and that you can put in Iraq tomorrow," said Beth Schissel, who graduated from the Air Force Academy in 1989 and went on to medical school.

Schissel was forced out of the military after she acknowledged that she was gay.

According to figures compiled by the Pentagon and released by the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military, Schissel is one of 244 medical and health professionals discharged from 1994 through 2003 under the policy that allows gays and lesbians to serve as long as they abstain from homosexual activity and do not disclose their sexual orientation. Congress approved the policy in 1993.

There were 137 officers discharged during that period. The database compiled by the Pentagon does not include names, but it appears that about 30 of the medical personnel who were discharged may also be included in the list of officers.

The center _ a research unit of the Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research of the University of California _ promotes analysis of the issue of gays in the military.

"These discharges comprise a very small percentage of the total and should be viewed in that context," said Lt. Col. Ellen Krenke, a Pentagon spokeswoman. She added that troops discharged under the law can continue to serve their country by becoming a private military contractor or working for other federal agencies.

Opponents of the policy on gays acknowledge that the number of those discharged is small. But they say the policy exacerbates a shortage of medical specialists in the military when they are needed the most.

Late last year Army officials acknowledged in a congressional hearing that they are seeing shortfalls in key medical specialties.

"What advantage is the military getting by firing brain surgeons at the very time our wounded soldiers aren't receiving the medical care they need?" said Aaron Belkin, associate professor of political science at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Overall, the number of discharges has gone down in recent years.

"When we're at war, commanders know that gay personnel are just as important as any other personnel," said Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow at the Center. He said that in some instances commanders knew someone in their unit was gay but ignored it.

The overall discharges peaked in 2000 and 2001, on the heels of the 1999 murder of Pfc. Barry Winchell, who was bludgeoned to death by a fellow soldier at Fort Campbell, Ky., who believed Winchell was gay. About one-sixth of the discharges in 2001 were at that base.

Officials did not provide estimates on the cost of a military education or one for medical personnel. However, according to the private American Medical Student Association, average annual tuition and fees at public and private U.S. medical schools in 2002 were $14,577 and $30,960, respectively.

Early last year the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, estimated it cost the Pentagon nearly $200 million to recruit and train replacements for the nearly 9,500 troops that had to leave the military because of the policy. The losses included hundreds of highly skilled troops, including translators, between 1994 through 2003.

Opponents of the policy are backing legislation in the House sponsored by Rep. Marty Meehan, D-Mass., that would repeal the law. But that bill _ with 107 co-sponsors _ is considered a longshot in the Republican-controlled House.

Copyright 2006 Associated Press.

Monday, January 23, 2006

Phoebe and Evolution

Monkeys...Darwin....It's a nice story..........Just don't get her started on gravity.

Friday, January 20, 2006

JOHN KERRY HAS FALLEN....

JOHN KERRY HAS FALLEN…AND KEEPS GETTING UP

Too bad people in his own party want to put him on ice

By Michael Crowley

"He’s under the illusion that over 50 million Americans voted for him, as opposed to the reality that they voted against George W. Bush.”

In late November, George W. Bush went on the political offensive over the state of the war in Iraq. Determined to get his groove back after weeks of being pummeled by revitalized Democrats, Bush delivered a major speech outlining his “plan for victory.” Democrats, smelling blood, carefully plotted their response. The party’s Senate leadership decided that Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island would deliver their rebuttal. As a former member of the Eighty-second Airborne who had opposed the war from the start, Reed had the perfect credentials to remind Americans about Bush’s mismanagement of the war and of the grim realities the president had refused to acknowledge in his speech. All things considered, it looked like a banner opportunity to inflict more damage on the reeling president.

There was just one problem: John Kerry.

Without checking with his party’s leaders, Kerry scheduled his own response to Bush, which was to take place at 11 A.M., precisely the time that Reed was scheduled to respond. In Senate strategy meetings, mild panic ensued. “It was ‘Oh shit, we can’t have two competing press conferences at the same time,’ ” a senior Senate aide told me recently. “Many calls were made between offices in an effort to make sure we didn’t have two competing events with two messages, because we had ours pretty well fleshed out.” Rather than make way for Reed, though, Kerry agreed to appear with him at a joint press event. Plenty of Democrats predicted what came next: Kerry was “droney and repetitive,” the aide says, but the press nevertheless overlooked Reed and went with the story line of Kerry, yesterday’s Democrat, still taking swings at the guy who beat him. “Jack Reed did a great job, but in the end he was overshadowed by John Kerry,” said the aide. “The story fell into the lazy narrative of John Kerry versus George Bush on Iraq, and that’s not where we wanted to go.”

The bitter clincher came on that night’s Daily Show. After riffing on the Bush speech, Jon Stewart turned his attention to the Democrats. “Naturally, the political opposition would pounce on the president’s vulnerability by choosing as their spokesman an inspiring rhetorical speaker with the proven ability to defeat the president,” Stewart said. Cut to a shot of Kerry stammering, then back to Stewart. “Kerry? You went with Kerry?”

After more footage of Kerry rambling incomprehensibly, Stewart stared at the camera and screamed, “No one understands you!” The next day, a link to the clip bounced among the e-mail accounts of angry Senate Democratic staffers.

So it goes for the man who, a year ago, was 60,000 Ohio votes short of learning the nuclear codes. His party is finally finding its voice and tormenting Republicans on everything from Katrina to Iraq to the seedy corruption revealed in the Tom DeLay/Jack Abramoff/Duke Cunningham scandals. But Kerry—who Democrats almost unanimously say is keenly interested in running for president again in 2008—keeps reminding people of the bad old days, when the country had a choice and chose Bush. “There was so much pent-up anti-Bush anger that has not dissipated,” says Carter Eskew, former chief strategist to Al Gore in 2000. “There was no catharsis, and he’s a reminder of that frustration and anger.”

Don’t think Republicans fail to get this. When Bush delivered an earlier Iraq speech, he took a conspicuous swipe at Kerry, quoting from the senator’s remarks just before he voted to authorize the Iraq war. (Kerry had said that “a deadly arsenal of weapons of mass destruction in [Saddam Hussein’s] hands is a real and grave threat to our security.” Not very convenient for Democrats saying the WMD threat was a White House lie.) But Kerry’s office was delighted by the attention. “Republicans are going after him because they are scared of the support he has inside the party,” says Kerry consultant Jenny Backus. But that reaction is like a battered wife who’d rather be abused than ignored. Clearly, even though Kerry came oh so close in the election, Republicans don’t think he stands up well in the public’s memory, and they’re more than happy to address him as the face of the Democratic Party.

Which is why, as another frustrated senior Democratic strategist puts it, “congressional Democrats are spending an awful lot of time trying to figure out how to maneuver around him. They want some new ground. They want the basis for a new conversation. And Kerry’s very much stuck in reverse. It causes a lot of resentment.”

*****

For a brief golden October afternoon in Washington, D.C., precisely fifty-one weeks after the 2004 presidential election, the past was indeed present, at least in the mind of John Kerry. A crowd filled Georgetown University’s Gaston Hall for what had been billed as a “major address” by Kerry on Iraq. There was the battery of TV cameras, the stand of American flags, Teresa in the front row, and Marvin Nicholson Jr., Kerry’s “body man” from the ’04 campaign, adjusting the mike the way he’d done a thousand times before.

In came Kerry, slim and straight as an ironing board, with that rectangular coif of silver hair. But there was something else, too, a subtle sheepishness in the body language, a certain lilt to his grin, something intangible that seemed to say, I’m sorry, folks.

“Whatever else might be said about the campaign,” said the Georgetown professor introducing Kerry, “he certainly fought it hard and honorably.” Whatever else might be said? There’s plenty else that might be said. On that day, in fact, in that very room, people were saying it. “So he’s finally come up with an Iraq policy!” one reporter sitting in the back offered with a grin.

As Kerry took the podium, you couldn’t help but wonder how he’d break the ice and cut through the unavoidable awkwardness. Al Gore was surprisingly expert at this back in 2001, cracking that he used to be the next president of the United States. But Kerry seemed incapable of mustering a good joke. “I had thought about coming back here in a different role,” he said with a wan look on his face. “But I’m honored to be back.” Clang. Maybe the wounds are still too raw for self-effacing humor. Or maybe self-effacing just isn’t his thing.

To be fair, Kerry’s speech wasn’t half bad. “For misleading a nation into war, they will be indicted in the high court of history!” he thundered, and then he referred to Iraq as “one of the greatest foreign-policy misadventures of all time.” It made you wonder where this guy was back in 2004. But then the Georgetown kids lined up to ask questions, and the pain of it all came rushing back. Kerry’s responses were brutally long-winded, as if he were intent on slowly suffocating their earnestness with leaden filibusters. Eyes glazed. Yawns unfolded. Even the kids at the mike shifted their weight impatiently. Afterward, a few dozen students swarmed around Kerry, and he momentarily shifted into high glad-handing mode, soaking up the attention. Alas, the mutual love, such as it was, had to be cut short because of pressing business back in the Senate. “The senator’s only got twenty minutes on the vote!” announced Marvin, the genial body man, as he shooed people away. “He’s gotta go!” A budget amendment to increase spending on home-heating oil awaited him.

In presidential politics, defeat is usually total. Salvaging dignity and honor is no easy task, and by historical standards John Kerry has actually had it pretty good. Better than an instant punch line like Dukakis or Viagra salesman Bob Dole.

But it can’t be fun, either. “He’s gone from being the guy in the bubble entourage of 150 to being one of a hundred senators,” says one former Kerry aide. “That transition is not an easy one, I wouldn’t think.”

A Senate staffer adds, “There is this weird cognitive dissonance. You see Kerry in the Dirksen [Senate Office Building] cafeteria getting a salad, and you think, You were inches from becoming president, and now you’re getting your own salad. And it’s not even a good salad!”

Kerry was never much of a team player in the Senate, and staffers there say that hasn’t changed. When he returned to the Senate after the election, his Democratic colleagues respectfully thanked him, but they didn’t ask him to be their spiritual leader. He was just…back. Since then he’s been reserved in meetings with his fellow Democratic senators, and off the Senate floor reporters generally let him pass unmolested. The smallness of the job must hound him. Back in October, massive flooding that threatened to burst a dam in the industrial Massachusetts town of Taunton forced him to fly up there and help oversee his constituents’ crisis. Kerry’s aides say this is to his credit—it shows he believes in his work. “He didn’t need to come back to the Senate,” says David Wade, Kerry’s press secretary. “He likes his job.”

But never mind the present. Kerry, it seems, is still living in the past. He remembers the 59 million votes he received, more than any other presidential candidate in history—except for the guy who got 62 million that same day. He remembers the hours on election day when exit polls had him winning easily. He remembers his media guy, Bob Shrum, in a regrettably heady early-evening moment, addressing him as “Mr. President.” Mr. President. To hear those words must be something like an acid trip that went too far. You’re just never quite the same again.

Instead, Kerry has become just one of a slew of Democrats cluttering up the party’s message, complicating efforts to present a unified opposition against the president. “Normally, he would be the titular head of the opposition, but he’s not, so we have this kind of ten-headed monster that’s out there,” says Mike McCurry, a former Clinton press secretary and senior adviser to Kerry in the late days of his campaign. McCurry, who remains fond of Kerry, says of him (and of the various other Democrats who seem to be already running for president): “People have to stop freelancing. The reason people think Democrats have nothing to say is that we have fifty people saying fifty different things.” Kerry’s not the only offender, McCurry notes. But plenty of other Democrats say he’s the main one.

Party leaders might be warmer to Kerry if there were much evidence that Democrats still considered him their standard-bearer. But there isn’t. When asked in a November NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey whom they would support in the 2008 primaries, Kerry was Democratic voters’ fourth choice. Hillary Clinton blew everyone away with 41 percent. Kerry’s former running mate, John Edwards, got 14 percent. Even Al Gore, who’s almost surely not running, tallied 12 percent. Kerry? He clocked in at a measly 10 percent—lower even than the number of people who said they definitely would not vote for him again in the next Democratic primary.

Kerry aides consider such polls “utterly meaningless,” insisting he is still loved outside the Beltway. “People in airports walk up to him saying, ‘I should have voted for you’ or ‘I’m so glad you’re still out there,’ ” Backus says.

But it’s in the sanctum of strategists, moneymen, and influential activists who control the party that Kerry fares the worst. These are the people who feel Kerry blew his best chance and that he’s “delusional,” as I repeatedly heard, to think he’s still wanted.

“He thinks it’s about him,” says a former Kerry campaign aide who had significant responsibilities in a key swing state. “He thinks all those people worked so hard and gave so much of their time because of him. And that is a gross misreading of the situation. I think he’s under the illusion that over 50 million Americans voted for him, as opposed to the reality that they voted against George W. Bush.”

Joe Lockhart says, “I don’t think there have been many people in the last year who have been sitting around saying, ‘Now that he has this practice under his belt, boy, in 2008 he’s gonna blow the doors off!’ ”

Another big-name Democrat who is close to party activists and donors, and who worked hard for Kerry in 2004, is even harsher: “Nobody has enthusiasm for him. We should have won that last time. He was running against that idiot.” (“We were running against an incumbent president in wartime,” counters Backus. “It was a challenge for any Democrat.”)

Kerry aides admit their man has never been loved by Washington insiders, but, Wade says, “I think you have to distinguish between inside Washington and outside Washington.” And there are those who insist you can’t underestimate how much he learned from running once. It’s a point Kerry himself makes. “If I get into that race,” he told CNN last November, “having learned what I’ve learned, and the experience I had last year, I think I know how to do what I need to do, and I will run to win.”

Kerry does have a Rolodex thick with the names of rich Democrats. And he’s got an e-mail list of 3 million Democratic activists. “Anybody who writes him off is a fool,” says Jim Jordan.

Several Democrats told me that they worry that Kerry doesn’t have anyone around who is willing to give him a candid assessment of his chances. “I don’t think John Kerry has a lot of really close friends in politics,” says a former adviser to Kerry’s campaign. “I don’t see a lot of people going to him and saying, ‘John, for the sake of your own pride, don’t do this.’ ”

“My guess,” says another veteran Democratic strategist, “is that a bunch of those money guys are telling John that they’re with him—and they’re waiting for Hillary Clinton to call.”

*****

Proof that God is a comedian: In November of last year, Kerry was called for jury duty in Boston’s Suffolk Superior Court. Somehow he actually made it onto the jury, for a case in which two men were suing the city for injuries sustained in an accident involving a school principal. Kerry was even chosen to be jury foreman. Thus were born dozens of snickering headlines noting that, one year after November 2004, John Kerry had finally won an election. Such are the indignities of life for a defeated nominee.

It’s enough to make you feel sorry for the guy. But then you remember the $87 billion quote, and the turgid speeches, and the Swift Boat debacle, and your empathy turns to anger.

Clearly, Kerry’s fellow Democrats aren’t about to forget any of that soon. Even a media strategist who likes and sympathizes with Kerry concedes: “People inside the Beltway want him to, like they say in Harry Potter’s world, disappearate.”

Sometimes they act like he already has. I vividly recall a moment on the Senate floor one afternoon in the spring of 2005. A dramatic showdown was under way over judicial nominations, with Republicans threatening to invoke their dreaded “nuclear option” and change the Senate’s rules so Democrats couldn’t filibuster judges. A large circle of Democrats had formed on the Senate floor, including key party leaders like Harry Reid, Richard Durbin, and Hillary Clinton, and there they held an animated conversation. Kerry ambled up and stood just outside the circle a couple of feet behind Reid, clearly wanting to join in. But like a cocktail-party clique that rejects a dullard, the group didn’t part to welcome him. In fact, no one paid him any attention at all.

Perhaps it was an insignificant moment. Or maybe it symbolized something important: a general sense among Democrats that no one is particularly interested in hearing from John Kerry anymore.

Either way, the circle of senators remained closed, and after a few more moments, John Kerry, the man who for a few hours on November 2, 2004, believed he was president of the United States, looked around awkwardly and tugged at his shirtsleeve. Then, finally, he did the thing that he hasn’t been able to bring himself to do on the larger stage. He put his head down and walked away.

MICHAEL CROWLEY is a senior editor at The New Republic.

Too bad people in his own party want to put him on ice

By Michael Crowley

"He’s under the illusion that over 50 million Americans voted for him, as opposed to the reality that they voted against George W. Bush.”

In late November, George W. Bush went on the political offensive over the state of the war in Iraq. Determined to get his groove back after weeks of being pummeled by revitalized Democrats, Bush delivered a major speech outlining his “plan for victory.” Democrats, smelling blood, carefully plotted their response. The party’s Senate leadership decided that Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island would deliver their rebuttal. As a former member of the Eighty-second Airborne who had opposed the war from the start, Reed had the perfect credentials to remind Americans about Bush’s mismanagement of the war and of the grim realities the president had refused to acknowledge in his speech. All things considered, it looked like a banner opportunity to inflict more damage on the reeling president.

There was just one problem: John Kerry.

Without checking with his party’s leaders, Kerry scheduled his own response to Bush, which was to take place at 11 A.M., precisely the time that Reed was scheduled to respond. In Senate strategy meetings, mild panic ensued. “It was ‘Oh shit, we can’t have two competing press conferences at the same time,’ ” a senior Senate aide told me recently. “Many calls were made between offices in an effort to make sure we didn’t have two competing events with two messages, because we had ours pretty well fleshed out.” Rather than make way for Reed, though, Kerry agreed to appear with him at a joint press event. Plenty of Democrats predicted what came next: Kerry was “droney and repetitive,” the aide says, but the press nevertheless overlooked Reed and went with the story line of Kerry, yesterday’s Democrat, still taking swings at the guy who beat him. “Jack Reed did a great job, but in the end he was overshadowed by John Kerry,” said the aide. “The story fell into the lazy narrative of John Kerry versus George Bush on Iraq, and that’s not where we wanted to go.”

The bitter clincher came on that night’s Daily Show. After riffing on the Bush speech, Jon Stewart turned his attention to the Democrats. “Naturally, the political opposition would pounce on the president’s vulnerability by choosing as their spokesman an inspiring rhetorical speaker with the proven ability to defeat the president,” Stewart said. Cut to a shot of Kerry stammering, then back to Stewart. “Kerry? You went with Kerry?”

After more footage of Kerry rambling incomprehensibly, Stewart stared at the camera and screamed, “No one understands you!” The next day, a link to the clip bounced among the e-mail accounts of angry Senate Democratic staffers.

So it goes for the man who, a year ago, was 60,000 Ohio votes short of learning the nuclear codes. His party is finally finding its voice and tormenting Republicans on everything from Katrina to Iraq to the seedy corruption revealed in the Tom DeLay/Jack Abramoff/Duke Cunningham scandals. But Kerry—who Democrats almost unanimously say is keenly interested in running for president again in 2008—keeps reminding people of the bad old days, when the country had a choice and chose Bush. “There was so much pent-up anti-Bush anger that has not dissipated,” says Carter Eskew, former chief strategist to Al Gore in 2000. “There was no catharsis, and he’s a reminder of that frustration and anger.”

Don’t think Republicans fail to get this. When Bush delivered an earlier Iraq speech, he took a conspicuous swipe at Kerry, quoting from the senator’s remarks just before he voted to authorize the Iraq war. (Kerry had said that “a deadly arsenal of weapons of mass destruction in [Saddam Hussein’s] hands is a real and grave threat to our security.” Not very convenient for Democrats saying the WMD threat was a White House lie.) But Kerry’s office was delighted by the attention. “Republicans are going after him because they are scared of the support he has inside the party,” says Kerry consultant Jenny Backus. But that reaction is like a battered wife who’d rather be abused than ignored. Clearly, even though Kerry came oh so close in the election, Republicans don’t think he stands up well in the public’s memory, and they’re more than happy to address him as the face of the Democratic Party.

Which is why, as another frustrated senior Democratic strategist puts it, “congressional Democrats are spending an awful lot of time trying to figure out how to maneuver around him. They want some new ground. They want the basis for a new conversation. And Kerry’s very much stuck in reverse. It causes a lot of resentment.”

*****

For a brief golden October afternoon in Washington, D.C., precisely fifty-one weeks after the 2004 presidential election, the past was indeed present, at least in the mind of John Kerry. A crowd filled Georgetown University’s Gaston Hall for what had been billed as a “major address” by Kerry on Iraq. There was the battery of TV cameras, the stand of American flags, Teresa in the front row, and Marvin Nicholson Jr., Kerry’s “body man” from the ’04 campaign, adjusting the mike the way he’d done a thousand times before.

In came Kerry, slim and straight as an ironing board, with that rectangular coif of silver hair. But there was something else, too, a subtle sheepishness in the body language, a certain lilt to his grin, something intangible that seemed to say, I’m sorry, folks.

“Whatever else might be said about the campaign,” said the Georgetown professor introducing Kerry, “he certainly fought it hard and honorably.” Whatever else might be said? There’s plenty else that might be said. On that day, in fact, in that very room, people were saying it. “So he’s finally come up with an Iraq policy!” one reporter sitting in the back offered with a grin.

As Kerry took the podium, you couldn’t help but wonder how he’d break the ice and cut through the unavoidable awkwardness. Al Gore was surprisingly expert at this back in 2001, cracking that he used to be the next president of the United States. But Kerry seemed incapable of mustering a good joke. “I had thought about coming back here in a different role,” he said with a wan look on his face. “But I’m honored to be back.” Clang. Maybe the wounds are still too raw for self-effacing humor. Or maybe self-effacing just isn’t his thing.

To be fair, Kerry’s speech wasn’t half bad. “For misleading a nation into war, they will be indicted in the high court of history!” he thundered, and then he referred to Iraq as “one of the greatest foreign-policy misadventures of all time.” It made you wonder where this guy was back in 2004. But then the Georgetown kids lined up to ask questions, and the pain of it all came rushing back. Kerry’s responses were brutally long-winded, as if he were intent on slowly suffocating their earnestness with leaden filibusters. Eyes glazed. Yawns unfolded. Even the kids at the mike shifted their weight impatiently. Afterward, a few dozen students swarmed around Kerry, and he momentarily shifted into high glad-handing mode, soaking up the attention. Alas, the mutual love, such as it was, had to be cut short because of pressing business back in the Senate. “The senator’s only got twenty minutes on the vote!” announced Marvin, the genial body man, as he shooed people away. “He’s gotta go!” A budget amendment to increase spending on home-heating oil awaited him.

In presidential politics, defeat is usually total. Salvaging dignity and honor is no easy task, and by historical standards John Kerry has actually had it pretty good. Better than an instant punch line like Dukakis or Viagra salesman Bob Dole.

But it can’t be fun, either. “He’s gone from being the guy in the bubble entourage of 150 to being one of a hundred senators,” says one former Kerry aide. “That transition is not an easy one, I wouldn’t think.”

A Senate staffer adds, “There is this weird cognitive dissonance. You see Kerry in the Dirksen [Senate Office Building] cafeteria getting a salad, and you think, You were inches from becoming president, and now you’re getting your own salad. And it’s not even a good salad!”

Kerry was never much of a team player in the Senate, and staffers there say that hasn’t changed. When he returned to the Senate after the election, his Democratic colleagues respectfully thanked him, but they didn’t ask him to be their spiritual leader. He was just…back. Since then he’s been reserved in meetings with his fellow Democratic senators, and off the Senate floor reporters generally let him pass unmolested. The smallness of the job must hound him. Back in October, massive flooding that threatened to burst a dam in the industrial Massachusetts town of Taunton forced him to fly up there and help oversee his constituents’ crisis. Kerry’s aides say this is to his credit—it shows he believes in his work. “He didn’t need to come back to the Senate,” says David Wade, Kerry’s press secretary. “He likes his job.”

But never mind the present. Kerry, it seems, is still living in the past. He remembers the 59 million votes he received, more than any other presidential candidate in history—except for the guy who got 62 million that same day. He remembers the hours on election day when exit polls had him winning easily. He remembers his media guy, Bob Shrum, in a regrettably heady early-evening moment, addressing him as “Mr. President.” Mr. President. To hear those words must be something like an acid trip that went too far. You’re just never quite the same again.

Instead, Kerry has become just one of a slew of Democrats cluttering up the party’s message, complicating efforts to present a unified opposition against the president. “Normally, he would be the titular head of the opposition, but he’s not, so we have this kind of ten-headed monster that’s out there,” says Mike McCurry, a former Clinton press secretary and senior adviser to Kerry in the late days of his campaign. McCurry, who remains fond of Kerry, says of him (and of the various other Democrats who seem to be already running for president): “People have to stop freelancing. The reason people think Democrats have nothing to say is that we have fifty people saying fifty different things.” Kerry’s not the only offender, McCurry notes. But plenty of other Democrats say he’s the main one.

Party leaders might be warmer to Kerry if there were much evidence that Democrats still considered him their standard-bearer. But there isn’t. When asked in a November NBC News/Wall Street Journal survey whom they would support in the 2008 primaries, Kerry was Democratic voters’ fourth choice. Hillary Clinton blew everyone away with 41 percent. Kerry’s former running mate, John Edwards, got 14 percent. Even Al Gore, who’s almost surely not running, tallied 12 percent. Kerry? He clocked in at a measly 10 percent—lower even than the number of people who said they definitely would not vote for him again in the next Democratic primary.

Kerry aides consider such polls “utterly meaningless,” insisting he is still loved outside the Beltway. “People in airports walk up to him saying, ‘I should have voted for you’ or ‘I’m so glad you’re still out there,’ ” Backus says.

But it’s in the sanctum of strategists, moneymen, and influential activists who control the party that Kerry fares the worst. These are the people who feel Kerry blew his best chance and that he’s “delusional,” as I repeatedly heard, to think he’s still wanted.

“He thinks it’s about him,” says a former Kerry campaign aide who had significant responsibilities in a key swing state. “He thinks all those people worked so hard and gave so much of their time because of him. And that is a gross misreading of the situation. I think he’s under the illusion that over 50 million Americans voted for him, as opposed to the reality that they voted against George W. Bush.”

Joe Lockhart says, “I don’t think there have been many people in the last year who have been sitting around saying, ‘Now that he has this practice under his belt, boy, in 2008 he’s gonna blow the doors off!’ ”

Another big-name Democrat who is close to party activists and donors, and who worked hard for Kerry in 2004, is even harsher: “Nobody has enthusiasm for him. We should have won that last time. He was running against that idiot.” (“We were running against an incumbent president in wartime,” counters Backus. “It was a challenge for any Democrat.”)

Kerry aides admit their man has never been loved by Washington insiders, but, Wade says, “I think you have to distinguish between inside Washington and outside Washington.” And there are those who insist you can’t underestimate how much he learned from running once. It’s a point Kerry himself makes. “If I get into that race,” he told CNN last November, “having learned what I’ve learned, and the experience I had last year, I think I know how to do what I need to do, and I will run to win.”

Kerry does have a Rolodex thick with the names of rich Democrats. And he’s got an e-mail list of 3 million Democratic activists. “Anybody who writes him off is a fool,” says Jim Jordan.

Several Democrats told me that they worry that Kerry doesn’t have anyone around who is willing to give him a candid assessment of his chances. “I don’t think John Kerry has a lot of really close friends in politics,” says a former adviser to Kerry’s campaign. “I don’t see a lot of people going to him and saying, ‘John, for the sake of your own pride, don’t do this.’ ”

“My guess,” says another veteran Democratic strategist, “is that a bunch of those money guys are telling John that they’re with him—and they’re waiting for Hillary Clinton to call.”

*****

Proof that God is a comedian: In November of last year, Kerry was called for jury duty in Boston’s Suffolk Superior Court. Somehow he actually made it onto the jury, for a case in which two men were suing the city for injuries sustained in an accident involving a school principal. Kerry was even chosen to be jury foreman. Thus were born dozens of snickering headlines noting that, one year after November 2004, John Kerry had finally won an election. Such are the indignities of life for a defeated nominee.

It’s enough to make you feel sorry for the guy. But then you remember the $87 billion quote, and the turgid speeches, and the Swift Boat debacle, and your empathy turns to anger.

Clearly, Kerry’s fellow Democrats aren’t about to forget any of that soon. Even a media strategist who likes and sympathizes with Kerry concedes: “People inside the Beltway want him to, like they say in Harry Potter’s world, disappearate.”